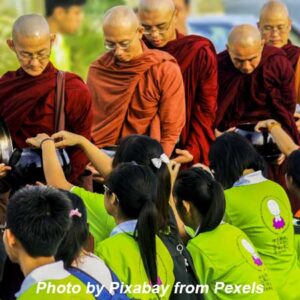

My teacher at the 6-day mindfulness retreat about which I wrote last week trained at a Buddhist Forest temple in Thailand. Each day, the monks would line up in order of seniority and walk to the village to beg for alms (rice, meat, fish, vegetables, fruit). No matter how little they had, the villagers gave generously because they valued the monks’ work. Having filled their begging bowls, the monks returned to the monastery to listen to a dharma talk, eat their meal for the day, and meditate. They might break in the afternoon to do chores and have a cup of tea. Periodically, they’d gather to chant the 227 precepts and confess any deviations from them. When the moon was full, they remained wakeful and meditated through the night. It was a simple life that dated back 1,000 years.

My teacher at the 6-day mindfulness retreat about which I wrote last week trained at a Buddhist Forest temple in Thailand. Each day, the monks would line up in order of seniority and walk to the village to beg for alms (rice, meat, fish, vegetables, fruit). No matter how little they had, the villagers gave generously because they valued the monks’ work. Having filled their begging bowls, the monks returned to the monastery to listen to a dharma talk, eat their meal for the day, and meditate. They might break in the afternoon to do chores and have a cup of tea. Periodically, they’d gather to chant the 227 precepts and confess any deviations from them. When the moon was full, they remained wakeful and meditated through the night. It was a simple life that dated back 1,000 years.

After leaving the monastery, he became a licensed therapist and trauma counsellor and has served his clients and community faithfully for decades. He remains a practicing Buddhist and dharma teacher. I was surprised to discover that he freely accepts participants to his retreats for a nominal registration fee. While nothing more is required, he provides an opportunity for the experience of giving. He writes:

“In accordance with Buddhist traditions, the teaching, guidance and other services of this retreat were given as dana. Dana is not a donation, which is what one gives to organisations and individuals in need. Dana refers to the economy of generosity where the teachings and services are given freely and those who receive the teaching have the opportunity to reciprocate with a financial gift that they feel is suitable after the retreat has been completed.

“The aim of dana is to cultivate joy from generosity. The amount you choose to give or not give is completely up to you. If you give too much resulting in difficulty, hardship, and regrets for yourself, then it defeats the purpose. Conversely, if you would like to give and do not, or give what is in your mind as very little, then again the function of dana is defeated.

“Dana is also a way of expressing one’s respect and gratitude for the value of the teachings. It is priceless and therefore a price cannot really be given to it. Remember, if you feel you would like to offer dana but have no money, offering the merits of your practice is also dana and as such something that we can all celebrate in.”

I am reminded of the widow’s offering in the Gospel of Mark 12:41-44. We read:

“Jesus sat down opposite the place where the offerings were put and watched the crowd putting their money into the temple treasury. Many rich people threw in large amounts. But a poor widow came and put in two very small copper coins, worth only a few cents. Calling his disciples to him, Jesus said, “Truly I tell you, this poor widow has put more into the treasury than all the others. They all gave out of their wealth; but she, out of her poverty, put in everything — all she had to live on.”

Both of these teachings call upon us to be intentional about sharing what we have been given. Such gifts should transcend transactional considerations – i.e., if I give this, then I will get that. They should transcend duty and obligation from which feelings of guilt might otherwise arise. They should transcend a scarcity mentality with its undergirding in fear.

Giving freely and generously from the heart confers benefit upon the giver and receiver. When I’m most caught up in anxiety or sadness, I look for opportunities to be generous. It boosts my spirits, softens my heart, and cultivates a quality of character that I want to inhabit.