As a former caregiver for nonagenarian parents, I’ve spent a good deal of energy consulting the experts on what it takes to sustain good physical, mental, and emotional health into old age. I’ve been putting that advice into practice in hopes that it will pay dividends as I continue racking up the years. My latest read dives into the psychology of aging with the intent of giving readers a new way to view and inhabit the journey.

In The Inner Work of Aging: Shifting From Role to Soul, Dr. Connie Zweig provides a process by which one becomes attuned to the soul’s inner longing and emerges as a vibrant spiritual elder. It’s a process of transformation from the inside out through which one confronts denial, resistance, and shadow personas en route to a vital and genuinely meaningful life.

In The Inner Work of Aging: Shifting From Role to Soul, Dr. Connie Zweig provides a process by which one becomes attuned to the soul’s inner longing and emerges as a vibrant spiritual elder. It’s a process of transformation from the inside out through which one confronts denial, resistance, and shadow personas en route to a vital and genuinely meaningful life.

In a highly youth-oriented culture, it’s no surprise that denial and resistance rear their ugly heads. I remember when young folks used to talk about never trusting anyone over thirty (which they now refer to as the “dirty thirty.”) Then there were the funerial decorations that went along with fortieth birthday parties. By 50, the jokes stopped being funny as folks started bumping up against job discrimination. By 60, there was the full-court press to sign up for anti-aging products and procedures that would help keep up youthful appearances. To the extent that we internalize these messages, we lose sight of the inner vibrancy that welcomes advancing years and the wisdom that comes with them.

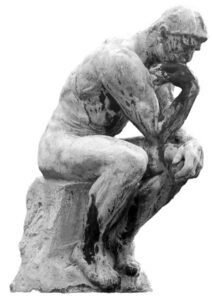

And what of the shadow personas? Our performance-oriented culture has us believing that we are what we do. So even if retirement becomes an option, we may still be so addicted to appearances that we drive ourselves to be “successful” in the eyes of our peers – perhaps on the volunteer stage, or the wild travel adventures stage, or whatever projects a winning image on social media. We may also be inured to caregiving and allow our unmet needs to go unnoticed.

Dr. Zweig shares three portals through which we can launch our inner journey:

- Shadow awareness helps us remove inner obstacles that block us from finding the treasures of late life. She provides lots of tools and examples to plumb theses depths.

- Pure awareness allows the silent, dispassionate witness to unfold. It is a state of mind that is silent, open, resting, and aware of awareness (a.k.a. mindfulness meditation). It brings us back to an experience of the present moment through the sensory doors.

- Mortality awareness calls us to live fully in the present with a keen awareness that our days are numbered.

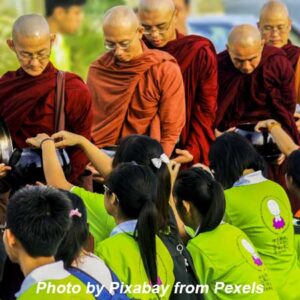

Two “divine messengers” may spur us on toward the inner path. Retirement disrupts our habitual patterns and offers the opportunity to explore new ways of being. For some, this newfound freedom may be paralyzing. They’ve become acclimated to their routines and have no idea what to do with themselves. They may profit from the wisdom and guidance of an experience coach. Others use the time to explore longstanding passions as well as new opportunities all the while listening to their inner voices to see what truly resonates.

Illness may also prove disruptive whether experiencing it as the afflicted or the caregiver. It’s a tricky teacher. It can be the doorway to profound lessons and insights so long as the affected individuals do not get stuck in martyr/victim roles. I’ve definitely trafficked in the latter. (It’s easy to do!) A change in attitude does not lessen the burden of an illness, but it can avoid the needless suffering that goes along with it.

Amidst all the thoughts, case studies, and exercise provided in the book, I took away the lesson that one’s elder years can be a deeply fulfilling journey of coming back to oneself and finding deep-seated contentment and purpose. While I haven’t reached the culmination of my inner journey, I can attest to the merits of its pursuit. Per Zweig, the rewards of the journey include:

- Spiritual depth

- Equanimity in the face of challenges

- Openness, rather than judgment and premature closure

- The ability to focus attention here and now

- Clarity unclouded by desire or fear

- Compassion for the suffering of others

- Big-picture knowledge

- Humility beyond ego