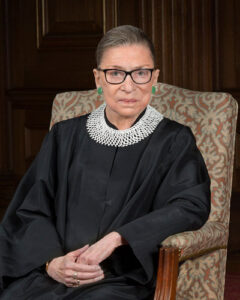

Twenty-seven years ago this week, Ruth Bader Ginsburg was sworn in as the 107th U.S. Supreme Court Justice. Her candidacy came on the heels of a stellar legal career as an academic proceduralist, a proven litigator and advocate for gender equality, and a thoughtful federal appellate judge.

Twenty-seven years ago this week, Ruth Bader Ginsburg was sworn in as the 107th U.S. Supreme Court Justice. Her candidacy came on the heels of a stellar legal career as an academic proceduralist, a proven litigator and advocate for gender equality, and a thoughtful federal appellate judge.

Joan Ruth Bader was born on March 15, 1933 in Brooklyn Heights to hard-working immigrant parents, Nathan and Celia. Older sister Marilyn dubbed her “Kiki” for being such a kicky baby, and the nickname stuck. Kiki never got the chance to know her only sibling. Marilyn died of spinal meningitis in June 1934.

Given an abundance of Joans in Brooklyn Public School 238, Kiki started using her middle name, Ruth, to avoid confusion. She earned straight As at PS238 while also attending Hebrew school, taking piano lessons, and feeding a voracious literary appetite. At James Madison High School, Ruth was an honor student, played cello in the school orchestra, and twirled baton.

Ruth entered Cornell University in Fall 1950 on a full scholarship. She was a dedicated student who aspired to achieve good grades and become successful upon graduation. Having excelled in a constitutional law class, her professor encouraged her to pursue law school and legal activism as a means of making the world better.

After graduation, Ruth married her college sweetheart, Marty Ginsburg. The couple spent two years in Oklahoma while Marty dispatched his military service obligation before both went to the Harvard Law School. As one of 8 women in a class of 552, Ruth stood out in the male-dominated culture and committed herself to a high standard of preparation and excellence.

After Marty’s graduation, the couple moved to New York City where he established a practice as a tax attorney. Ruth transferred to Columbia University as one of 12 women in a class of 341. She earned a place on the Columbia Law Review and tied for first in class upon graduation.

Post-graduation, Ruth secured a position as a law clerk for Judge Edmund L. Palmieri. While there, she accepted an assignment to research Swedish jurisprudence as part of a larger project on international procedures. Mentor Hans Smit bolstered her confidence and helped her establish a name for herself.

In September 1963, Ruth took on a teaching position at Rutgers University in civil procedure and comparative law. She also taught courses at New York University and volunteered her time at the New Jersey branch of the ACLU. The latter fueled her desire to participate actively in the civil rights movement and accorded her the opportunity to gain litigation experience. Rutgers made her a full tenured professor in 1969.

At the dawn of a new decade, Ruth was invited to teach a symposium on Women and the Law at Yale University. She researched the subject thoroughly and was disturbed by the law’s pervasive gender discrimination. It reflected the “separate spheres” mentality that assigned the roles of breadwinning and decision making to males and homemaking and child rearing to females. This construct was clearly out of step with increased participation of women in the workforce and a changing social consciousness toward the sexes. She decided to make sex-based discrimination her research specialty.

As the soon-to-be foremost litigator for gender equality, Ruth devised a strategy for presenting cases that would move the character of the prevailing courts. She used individual victories to set up favorable precedents. She was careful not to leap too far ahead of the political process and to align her cases with the weight of public opinion. Examples of cases that bear her fingerprints:

- Reed v. Reed overturned an Idaho statute that privileged fathers as the executors of their children’s estates.

- Frontiero v. Richardson determined that housing and medical benefits apportioned by the United States military could not be denied to the male dependent of a female officer.

- Struck v. Secretary of Defense challenged the military’s right to discharge a member of the armed services due to pregnancy.

During the 1970s, Ruth co-authored a book entitled Sex-Based Discrimination: Texts, Cases, and Materials and published 25 legal articles. She crafted 24 briefs in Supreme Court cases (9 for litigants and 15 as a friend of the court) and presented 6 oral arguments.

Upon the recommendation of President Jimmy Carter, Ruth Bader Ginsburg was sworn in as a Judge of DC Circuit Court of Appeals in 1980. Deemed a “paragon of judicial restraint,” she was a moderating influence on a fractious court and garnered respect for her intellectual rigor, caution, and collegiality.

With the retirement of Associate Justice Byron White in 1993, President Bill Clinton nominated Ruth Bader Ginsburg to serve as the 107th Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. The U.S. Senate endorsed her candidacy in a 96-3 vote, and she was sworn in as an Associate Justice on August 10, 1993.

In recent years, Justice Ginsburg has been cast in the role of the chief dissenter. Her opinions frequently land in the minority on civil rights, immigration, wage equality, women’s reproductive rights, faith-based programs, campaign finances, gun control, and the death penalty. Yet she soldiers on and lets her meticulously crafted dissents spur legislative action or appeal “to the intelligence of a future day.”

References

- Jane Sherron DeHart, Ruth Bader Ginsberg: A Life, New York: Vintage Books, ©2018

- Ruth Bader Ginsburg, My Own Words, New York: Simon & Shuster, ©2016

- Jeffrey Rosen, Conversations with RBG: Ruth Bader Ginsburg on Life, Love, Liberty, and Law, New York: Henry Hilt and Company, ©2019