“We are all born with a far more adaptable, all-purpose, opportunistic, brain than we have understood.” – Dr. Norman Doidge, MD

I’ve explored aspects of neuroscience in prior blog posts. My latest foray into the subject came through Norman Doidge’s book The Brain That Changes Itself: Stories of Personal Triumph from the Frontiers of Neuroscience. What I learned from his research made me all the more impressed by this amazing little organ.

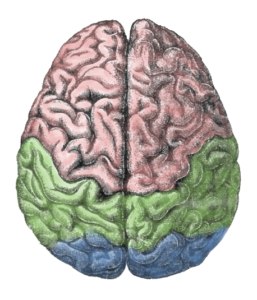

Most of realize that our brains are the master controllers for sustaining bodily functions, processing sensory input, and incubating consciousness. Yet we may not grasp the extent to which the brain alters its structure and function in response to thoughts, activities, and environmental factors. Scientists refer to this phenomenon as neuroplasticity – i.e., the neural network’s ability to change through growth and reorganization. Through it, we can improve mental activities, heal from injury, and establish robust routing systems that bypass blocked pathways as the need arises. With attentive effort, we can sustain this remarkable capacity to the end of our days.

Most of realize that our brains are the master controllers for sustaining bodily functions, processing sensory input, and incubating consciousness. Yet we may not grasp the extent to which the brain alters its structure and function in response to thoughts, activities, and environmental factors. Scientists refer to this phenomenon as neuroplasticity – i.e., the neural network’s ability to change through growth and reorganization. Through it, we can improve mental activities, heal from injury, and establish robust routing systems that bypass blocked pathways as the need arises. With attentive effort, we can sustain this remarkable capacity to the end of our days.

Much like physical fitness regimens, stimulating the brain makes it grow. Brain weight may increase up to 5% through mental training or life in enriched environments; targeted areas may increase up to 9%. This weight gain finds expression in stimulated neurons that increase in size, develop 25% more neural connections, and command increased blood supply. These “beefy neurons” become more efficient, taking less time and resource to perform tasks for which they’ve been trained. Powerful signals have greater impact on the brain.

A leading researcher on neuroplasticity, Dr. Michael Merzenich proved that substantive improvement in cognitive function is possible at any age. The key to success lies in giving the brain the right stimuli in the right order at the right time to drive plastic change. He says:

“When learning occurs in a way consistent with the laws that govern brain plasticity, the mental ‘machinery’ of the brain can be improved so that we learn and perceive with greater precision, speed, and retention.”

For example, through use of specially designed computer programs, users receive specific challenges that target their developmental needs and add difficulty at a pace consistent with their learning styles. Struggling learners at school may take advantage of Fast ForWord, an evidence-based, adaptive reading and language program that boasts 1-2 year gains in 40-60 hours of use. Merzenich’s BrainHQ offers 29 exercises that address attention, brain speed, memory, people skills, navigation, and intelligence.

Brain maps are neither static nor universal; we allocate neural capacity competitively. If one area goes dormant, another area will take it over. As such, if we stop using a skill, that brain map space will be placed in service of an active skill. It’s the law of the jungle: use it, or lose it. For example, a blind person cannot use the visual cortex to receive input from the eyes. That processing power may be repurposed to provide heightened sensitivity in hearing and touch. Unfortunately, if we stop exercising our analytical skills or creative capacities in favor of mindless activities, those vital cognitive resources will also be repurposed. Once a bad habit claims (and sustains) brain space, it can be difficult to dislodge.

The brain can reorganize itself after devastating injury so long as there is adjacent, healthy tissue that can be recruited to take over for lost function. Treatment must address both neural shock and learned nonuse. To that end, motivated patients put themselves through a series of physical and cognitive efforts to support their brains’ rewiring. Legendary actor Kirk Douglas famously worked his way back from his 1996 stroke and continued to act and publish. Actor Christopher Reeve regained a modicum of feeling and movement after sustaining a paralyzing spinal cord injury.

So why do so many of us lose brain function as we age?

Give the right combination of stimuli and experience, we are learning sponges throughout our childhood and teen years. As we grow into adulthood, we lean more heavily on mastered skills in lieu of acquiring new ones. By middle age, we’re settled into our careers and rarely engage in the kind of focused attention that produces long-term neural growth. In a word, we’re comfortable.

We’re also prone to be far less active physically than when we were young. Physical exercise elevates brain-derived neurotropic factor (BNDF), a substance that starts to wane as we age. BDNF plays a crucial role in neuroplastic changes by:

- Consolidating neural connections

- Promoting fatty growth around neurons to speed transmission times

- Helping the brain pay attention (and remember) through nucleus basalis activation

So, if you’d like to hang on to what you’ve got (or add to it), be prepared to challenge yourself throughout your life. Activities that involve deep concentration – e.g., reading/studying, learning a new language, developing proficiency on a musical instrument, playing complex board games, taking up dancing – have been associated with a lower risk of dementia. Effective use of imagination also helps. If hesitant to take action (or temporarily constrained to do so), visualize the activity in attentive detail. It strengthens the cognitive muscles and increases the speed at which you can attain competency when taking action.