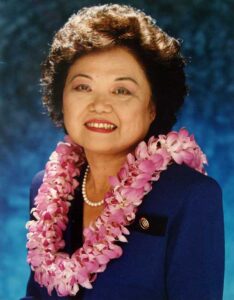

I haven’t placed a spotlight on an inspirational person for quite a while and decided to remedy that situation with a short bio on the first woman of color to be elected to serve in the United States Congress.

Patsy Matsu Takemoto was born on December 6, 1928 at a sugar plantation camp on the island of Maui. Her mother, Mitama Tateyama Takemoto, was a homemaker who raised Patsy and her older brother, Eugene. Her father, Suematsu Takemoto, was the first Japanese-American to graduate from the University of Hawaii and worked as a land surveyor for the East Maui Irrigation Company. The family moved to Honolulu after World War II when Suematsu established his own land surveying company.

Patsy Matsu Takemoto was born on December 6, 1928 at a sugar plantation camp on the island of Maui. Her mother, Mitama Tateyama Takemoto, was a homemaker who raised Patsy and her older brother, Eugene. Her father, Suematsu Takemoto, was the first Japanese-American to graduate from the University of Hawaii and worked as a land surveyor for the East Maui Irrigation Company. The family moved to Honolulu after World War II when Suematsu established his own land surveying company.

Patsy enrolled at the University of Hawaii with the intention of pursuing a career in medicine. Having earned bachelor degrees in zoology and chemistry in 1948, she secured placement as one of two women admitted to the University of Chicago Law School. While playing bridge one evening, she met a former U.S. Air Force navigator named John Francis Mink. The two fell in love and married in January 1951. That Spring, Patsy graduated with her Juris Doctor degree, and John received his Master’s Degree in geophysics.

Despite impressive credentials, Patsy faced employment discrimination as a female, married, Asian-American. She stayed on in her “student job” at the University of Chicago Law School library while her husband worked for U.S. Steel. The couple welcomed a baby daughter, Gwendolyn (Wendy), to the family in 1952. Having grown weary of Chicago winters, the family relocated to Hawaii. John found work with the Hawaiian Sugar Planters Association, and Patsy became the first Japanese-American woman licensed to practice law in the Territory of Hawaii.

Patsy had never taken much interest in politics beyond a resonance with the ideals espoused by Franklin Delano Roosevelt. The Territory of Hawaii had long been the province of Republican white businessmen who controlled the economic life of the islands. Weak leadership and internal dissention prevented the Democratic party from mounting a substantive challenge. In response to her participation in a series of meetings on Democratic platform reform, Patsy founded the Everyman Organization to give voice to a younger generation of voters.

With the advent of statehood, Hawaii held a special election to fill 3 seats in Congress (2 senate and 1 representative). Patsy hoped to secure the post as Hawaii’s representative but was defeated in the Democratic primary by the party’s preferred candidate, Daniel K. Inouye. When a second representative seat opened up for the United States Congress, Patsy tossed her hat into the ring and mounted a grassroots campaign with her husband as campaign manager. Though lacking support from the Democratic Party leadership, she eked out victories in the primary and general elections. On January 4, 1965, she was sworn into office by the Speaker of the House as the first Asian-American woman elected to Congress.

As a trailblazer in high political office, Patsy pursued her work with seriousness of purpose while being cognizant of stereotypes that anticipated quiet, self-effacing, acquiescent behavior. The media made things all the more difficult by referring to her as “the hula princess from Hawaii,” “the girl in the grass skirt, “and the “diminutive Patsy Mink.” She took such characterizations in stride and got about the business of governing.

Patsy’s appointment to the Education and Labor Committee gave her the opportunity to work on issues that mattered a great deal to her. She introduced legislation that would provide custodial care and educational development for pre-school children. Though opponents expressed concern about creating incentives for women to work outside the home, Patsy continued to work tirelessly in behalf of the working poor for whom work outside the home was an economic necessity.

A second term appointment to the Interior and Insular Affairs Committee gave Patsy the chance to support economic and political development of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands. She joined her fellow members of the Subcommittee on National Parks and Recreation on a visit to Hawaii’s Big Island where they discussed bills she’d sponsor to safeguard sacred Native Hawaiian sites. She thwarted the Corps of Engineers’ attempt to demolish the seawall of Kaloko, thereby preserving an important wetlands for native birds and presumed burial site of King Kamehameha. That site became the Kaloko-Honokohau National Park in 1978.

Patsy’s appointment to the Interior and Insular Affairs Committee also rekindled the fight to end nuclear testing in the Aleutian Islands. When denied access to documents believed to demonstrate government agency recommendations to cancel testing, she and 32 other members of Congress filed suit against the Environmental Protection Agency to compel disclosure. Though defeated in court, the case provided the impetus to strengthen key provisions in the Freedom of Information Act. This legislation set precedents that subsequently called for the release of President Nixon’s White House tapes during the Watergate inquiry.

Patsy was an early and vocal opponent to the Vietnam War. She objected to our involvement on moral grounds and found the secrecy surrounding our engagement unacceptable. She disturbed party leaders when voting against President Johnson’s military appropriations, believing the money would be better spent on domestic programs. She tossed her hat briefly into the 1972 Presidential election to provide a national forum for challenging Nixon’s lack of moral leadership and drive Democratic front-runner George McGovern toward an antiwar stance. She felt that she had to do everything possible to promote peace in Southeast Asia.

Patsy is perhaps best known as the co-author of Title IX of the Education Act Amendments of 1972. It prohibited discrimination on the basis of gender by educational institutions that receive federal funding. It covered areas such as recruitment and admission policies, financial aid, pregnancy, housing, and athletics. Though signed into law, controversy erupted when athletic departments at major universities came to terms with the reality of funding men’s and women’s programs equally. For the next three years, Patsy had to work doggedly to ensure that the provisions of Title IX would not be watered down by Congressional amendment or regulations issued by the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW). Her efforts paid off. In 1975, the final HEW regulations set forth the requirement that female athletes receive the same privileges and benefits that male athletes enjoyed.

In five re-election campaigns, Patsy faced tough primaries during which the local Democratic Party tried to oust her. She had strong opinions about her political agenda and would not be deterred from its pursuit by the party’s influence. She relied heavily on her supportive family and volunteers and mounted grassroots campaigns financed largely through small contributions.

In 1976, Patsy gave up a “sure bet” of a seventh Congressional term to pursue an open Senate seat. The old boy political network supported fellow House member Spark Matsunaga with financing, media coverage, and volunteers. This time, the party machinery proved too much, and Patsy was defeated.

With the untimely death of Senator Spark Matsunaga in 1990 and the appointment of Representative Danial Akaka to that seat, Patsy saw an opportunity to return to Congress. Though not the party’s preferred candidate, her “Experience of a Lifetime” campaign and impassioned belief in Democratic ideals won favor in the primary and general election.

Upon her return to Congress, Patsy found significant retrenchment in the legislation on which she’d labored years earlier. Where she’d once found her political ideals in the majority, she now fought uphill battles to gain traction for programs about which she was passionate. She advocated for universal health care long before it was passed into law by the Obama administration. She was an outspoken critic of the Republican-led welfare reform and fought to preserve safety nets for families and children. She authored the Family Stability and Work Act as an alternative welfare reform measure but was unable to secure the requisite support. She joined colleagues in successfully pressuring President Clinton to veto welfare bills in December 1995 and January 1996.

Late in her twelfth term as a United States Congresswoman, Patsy fell gravely ill with pneumonia. After a month’s hospitalization, she died on September 28, 2002 in Honolulu, Hawaii. She was re-elected by a wide margin in the November ballot. Democrat Ed Case went on to fill her seat following a special election. Colleague Norman Y. Mineta remembered her as “an American hero, a leader, and a trailblazer who made an irreplaceable mark in the fabric of our country.”